August 31

Rover is now snugly tucked away in covered storage in Lillehammer, Norway. We found a plumber who sold us some (unnamed) liquid to use as antifreeze to winterize our plumbing. He assured us it was non-toxic and would do the job. So, having no real alternative, we pumped it in and trust it will work.

We keep close track of our spending, and knew after only a few days of travel that this was going to be an expensive trip. And so it proved to be.

Still, we tried really hard not to be continually converting currency in our heads, and most of the time we succeeded. If we wanted, say, two cups of coffee, we were determined to simply pay the $10-$12 and not let it bother us.

Or not too much.

Details:

During our three months of travel, we spent $4900 on food (including wine). This was easily double what it would have cost at home: if we each had a simple sandwich and cup of coffee for lunch, the cost could easily be $25 to $30; an evening restaurant meal with a glass of wine was $80; a 3-liter box of cheap wine $50.

Campground costs were $2530. This is $12/night more than we paid last year and more than $20/night higher than our first trip, in 2008.

We were on the road 75 days: 64 nights in campgrounds and 10 in free sites (three in designated motorhome parking, seven in parking lots). The cheapest campground was $19.71 (with only electrical service); the most expensive $66.25 (a large family resort in Norway in high season). We averaged $40 a night, including electricity and shower costs. Nearly every site charged extra for electricity ($3-$7) and many did for showers as well (between $.75 and $1.50 for five minutes of hot water).

The quality of the campgrounds and facilities was generally very good. They all had toilet seats, toilet paper and outlets for hair dryers. Only twice did we have access to water at our site; only twice was there a picnic table; only once were we offered our own sewer connection (which we declined as an unnecessary expense). Not every campground could accommodate our waste system, but we had no problem finding places that could: Norway, for instance, has an extensive system of waste stations, all of them well signed, at gas stations and rest stops.

We always felt safe and even left Rover alone for five days in Helsinki, Finland, while we took a ferry to St. Petersburg, Russia. And the prize for the best campground goes to that campground in Helsinki. Each of its large pitches had both paving and grass, as well as hedges for privacy. Public transportation was right across the street, and the campground’s facilities were good and clean. Rover was there for 9 nights at a cost of $28/night (the price was discounted because of the length of our stay).

Gasoline cost $3999, an average of $9.30/gallon. The cheapest gas, if we figured it correctly, was in Russia: $4/gallon (but of course we did not have Rover with us to take advantage of it . . . or of the $6/gallon price in Estonia).

We covered 3542 miles during the three months. Rover gets 10 mpg, partly because even on divided highways we drove no faster than 50 mph (the speed limit in Scandinavia for vehicles our size).

We spent $71 on LP gas, which we use for cooking, running the refrigerator when we are not plugged in, and the furnace. We filled the tank at the beginning of the trip in Lillehammer and topped it off about a month later; when we put Rover in storage, we still had more than half a tank left. It was not a hot summer, so we actually ran the furnace occasionally for a few minutes, never used the air conditioner, and had blankets on our beds every night.

One of our largest expense category was $2050 for miscellaneous transportation. This included all buses, taxis, and parking fees, but was primarily the short ferries in Norway and the longer ones from Helsinki to Estonia and from Stockholm to Turku, Finland (this last one was $980 round trip, with Rover, including a private bedroom).

We spent another $2050 on museums, churches, tours, boat rides, concerts, etc.

Internet access came to $150. Sometimes the WiFi was free, at other times cheap . . . and occasionally it was ridiculously expensive. Also, its speed and reliability was often poor (but at least more and more campgrounds are realizing they need to make it available).

We spent a lot of money--$6000--before we even left home. These costs included airfare ($1900), the St Petersburg trip ($2070 for the hotel, transport, tours and overnight ferry), RV insurance ($1036) and the previously mentioned Stockholm/Finland ferry.

Although our expenses were highest in June, which we spent entirely in Norway, one of this trip’s two really good deals was also in Norway: the $561 we paid for storage for Rover in Lillehammer until next April or May. But our greatest surprise--and one we greeted with much relief--was getting home and opening the hospital bills for Susan’s emergency room visits, ambulance ride, four days in isolation, and lab tests: $3061! And that includes a CT scan! In the US, ten times that amount wouldn’t have surprised us. Even better, our insurance should cover most of it.

At $1800/week, this was easily our most expensive trip to date. But while that number sounds very big to us, we remind ourselves that our “at home” expenses during these three months were minimal and, had we chosen to stay home in the US, we’d have been spending at least $1000/week anyway.

Besides all that, having time with our granddaughter is priceless.

The scenery in Norway was worth a lot, too: there wasn’t a day when we didn’t come over a mountain or out of a tunnel and say, “Wow.” Sometimes it really did take our breath away. The weather was mostly good--cool, never hot, some rain--and we magically managed to avoid being out in the worst of it. The effect of the 20+ hours of daylight is very strange, and we were happy to get further south and later in the year to return to a more normal daylight schedule.

As always, we were grateful to the people we met who learned to speak English and, particularly this year, were impressed by how very fluent they usually were.

Other pluses: the coffee in the cafes was excellent; we saw more of the Tour de France than we could have hoped for; and as a result of Susan’s hospitalization, we saw more of the Olympics than we’d expected (although it was in Finnish).

Rover, our 24RB (Rear Bath) Born Free performed perfectly: she gave us no problems with any of the systems or engine, is freshly equipped with six Michelin tires ($2076 in Norway), and now has 69,793 miles on her odometer.

18,307 of those miles have been racked up in Europe during 14 months of travel on five trips, but we haven’t yet seen everything we want to. Our tentative plan for next year is to start from Lillehammer a little earlier than June and immediately head south through Sweden into Denmark and Germany (in preparation, David will be taking a refresher German II class through Adult Education). We hope you will come along again.

At Oslo's Opera House

August 22

As we came closer to Norway, the flat farm fields of Sweden changed to rocky wooded hills. Just before reaching the border, we stopped to fill up with gas at the lower Swedish prices. The station was located in a large shopping center where the parking lot was full of cars with Norwegian license plates. We also counted twenty motorhomes there. Everyone was stocking up at the lower prices. We bought just a couple of things at the grocery store, but the guy behind us had eight 2-lb. packages of ground beef.

We are now back on Norway’s toll roads. There were no tolls in Sweden or Finland, but in Norway you drive through toll cameras every 20 miles or so. If you are going to travel for several weeks in Norway as we did, it is necessary to set up an account with a credit card: the Norwegian authorities then charge a couple of hundred dollars to the card and subtract the toll from that amount every time we drive past one of their many cameras. If necessary, they load more money into the account. Eventually--well after the end of your travels--they refund what’s left over. We had set up an account before we began driving through Norway at the beginning of this year’s trip; later, we had to set up a second account before our return into the country a second time. As a result, we have no idea how much tolls have cost us, because it will take a while before the Norwegian authorities reimburse our credit card account.

We stopped for one more day (two nights) in Oslo. The campground was much less busy this time, we had no problem finding an electric hookup . . . and our view of the city wasn't blocked by other campers.

Also, getting to the campground this time, from the south and east, was a whole lot easier than approaching from the west and through the city had been a month ago. But if you are going to spend only one day in Oslo, don’t make it a Monday: anything worth visiting is closed.

On Tuesday we drove our final lap to Lillehammer.

At Lillehammer's Olympic ski jump.

Along the way we found two more caravan stores that didn’t have RV antifreeze. We thought we were about to buy a large quantity of the world’s most expensive vodka (taxes on alcohol here being very high). But David read an internet help site on which the answer to winterizing a cabin cruiser’s water system involved “plumber’s antifreeze”; at about the same time, someone suggested we speak to a plumber about how people in Norway winterize water lines in a summer cabin; we did, and were sold 3.5 liters of a concentrated, non-toxic, lightly tinted liquid we are supposed to dilute with a liter of water.

To celebrate, we then spent the day giving Rover a much-needed bath and interior cleaning.

We have travelled 3538 miles, and after we have returned home and added up all our kroner (both Swedish and Norwegian), euros, rubles and dollars, we will post a final blog entry in early September.

August 18

Winding our way west across southern Sweden, we have visited Nora, a small, mostly wooden one-story town, oozing charm, that has not yet burned to the ground. We also visited the castle in Örebro after finding a place to park Rover right alongside its moat in the center of the city. Later we drove just a little further into the town to Wadköping, another old handcraft village. Most of its buildings had been moved from elsewhere in the town to create the place. Unlike other similar places we’ve visited, nearly all of it was open, and it had a large used bookstore with an English section: always a popular find.

We stayed in Örebro that evening, in a huge resort campground where the receptionist just gave us a 24-hour internet password (even though the sign in the Reception had said we’d be charged for it). The next day we drove south to Kumla, to the largest shopping center in central Sweden, and then on to a shoe factory museum. The parking lots around the shopping centers have always been large and easy to maneuver, but finding parking in the center of these little towns is always a challenge. The shoe factory had its own little place for four cars, and Rover hung out just a bit on to the sidewalk . . . well, about 4 feet.

We are finding the still open campgrounds to be the large family-oriented resorts that cater to families during the Swedish vacation period. It seems to have ended in mid-August; in fact, one of the places we stayed at actually had closed down half the camping spots already. We drove on to Lidköping, stayed one night in the rain, and then drove north to the lovely Läckö Slott (Castle) standing out on a point on Vänern lake (and we certainly hope the purists among our readers appreciate the trouble we’ve taken to get the diacritic markings right!)

All of the detail inside the castle is original--and painted--no gold leaf here. Seeing it was worth driving the 30 miles on a country road. As we got nearer the castle, the path got more and more narrow. It was simply laid out over the terrain, up, down and around, not a tenth of a mile of it straight. But it was a good road just the same, well paved and not too bumpy, even through it offered no passing places.

We believe we had written earlier that the roads deteriorated when we left Norway and drove into Sweden. We take that back. The Swedish roads have been unfailingly excellent: wide, good shoulders, and well marked. (Of course, they do not have the Norwegian terrain to deal with.) One interesting driving regulation in Sweden calls for slower drivers to pull over when possible to let faster traffic pass. Some of the highways have wide shoulders just for that purpose, marked by broken white lines. The highway we were on today had shoulders sometimes almost the width of another full lane. We have had to detour on to country roads a few tmes and even those have been adequate and comfortable to drive Rover on.

When we return to Lillehammer we will have to winterize Rover’s fresh water plumbing system before we consign her to Norway’s dark winter storage. We have been unable to find the nontoxic RV water system antifreeze that is so easily available at home: people here just give us a blank stare when we ask for it. Today we found a RV shop big enough to qualify as Sweden’s equivalent to our Camping World . . . but even they didn’t know what we were asking for. We talked at length to the RV dealer onsite, who told us that the German motorhomes he sells are insulated for winter and that they simply blow the lines out. (He also asked to see Rover and took several pictures.) We have never done this (and aren’t sure we can find fittings that will work with our half-American, half-European water-and-compressed-air systems), so we’re still hoping we can find antifreeze or an alternative. Vodka, anyone?

August 14

It was David’s turn to feel sick: in his case, just really, really tired. So Susan drove out of Helsinki and all the way to Turku campground while David slept. Before we left the Helsinki campground, we filled the fresh water tank and dumped the black and gray water. This was the first time in 14 days that we had dumped--a record for us. But then Susan had been in the hospital for four of those days, and our St Petersburg trip kept us away for four nights. Still, we knew we were pushing our luck and decided to be careful lest we have to unplug and level again.

After sleeping for about 20 hours straight, David felt better again and we drove into Turku to visit their handicraft museum. This place is about a city block of 250-year-old wooden houses that survived the inevitable fire--this one in 1827--that had destroyed much of the city. The buildings are all in their original place and are now craft workshops and museums of a wide variety. More than half of the buildings were locked up, but it was still an interesting glimpse of what life had been like 250 years ago.

After that, we drove back to the hospital parking lot where we had parked for five nights while Susan was in the hospital. We wanted to be close to the ferry to Stockholm that was scheduled to sail early the next morning.

We were one of the last vehicles to be waved onboard the ferry . . . directed alongside a daunting row of 18-wheelers . . . just barely squeezing past . . . almost all the way to the bow of the ship . . . right in line to be one of the first ones off. We opted to shut down the refrigerator for the 12-hour trip rather than plug in to the ship’s generated current and risk some electrical problem like the one we’d had on the journey to Finland. (As it turned out, everything in the refrigerator seemed to survive without any problem.)

We had opted to pay a little extra for a private cabin (inboard; no window), so we would have a place to rest away from the many passengers who regarded the journey as a fine excuse to party--and the ship line, who encouraged this attitude by hiring Elvis-impersonators to entertain at 3:00 in the afternoon. Nevertheless, we did spend quite a bit of time at a good table right at the prow (but inside, protected from the wind). There is surprisingly little open water between Finland and Sweden, and from our table we could watch the ferry wending through the archipelago of rocky little islands as we left Turku. More than four hours later, we finally left them behind . . . only to soon be amid others like them as we approached Stockholm.

We were, indeed, one of the first off the ferry, and at the stoplight at the end of the wharf a sign directed us to the E4, so we were quickly on our way to Uppsala, 40 miles to the north. We found the city’s campground and chose a site outside its small Wifi zone rather than park closer to the antenna but next to a noisy group with children racing about and adults clearly planning a big outdoor party (do we sound like kill-joys, or what?). On Sunday we rode our bikes an easy ten minutes into the city, stopping first at the cathedral, where the choir was rehearsing for a service about to start. This cathedral is the largest in all of Scandinavia: red brick, undecorated, with two towers, each as high as the building is long.

Unlike its plain, unadorned exterior, the cathedral had quite a lot of painted detail inside. We stayed for the first part of the service, but sat way in the back so we could easily sneak out, since we didn’t think we could make it through an hour and a half service--or so it was billed--in Swedish! We went in search of museums, and even on a Sunday were able to find a couple that were open. One was the home and garden of Carl Linnaeus, the biologist responsible for some of the systematic taxonomy we all learned in Biology 101. It was a lovely “fireproof” home that had survived the fire of 1702 that destroyed much of that city. (How many places on this trip have we heard of a fire destroying an entire city? Everywhere we go, it seems.)

We fell in love with Uppsala. It is a lovely university town: tree-lined streets and boulevards, tree-lined riverfront, hundreds of bike racks filled with thousands of bicycles, flowers everywhere, students even more plentiful. It is hard to imagine it on a cold, dark midwinter day.

We stayed an extra night and went into the city again and visited the Carolina Rediviva (university library), where there is a Bible from the 6th century. And then, duly edified, we walked the shopping streets with everyone else.

We are heading east now, back to Norway. We are in Hallestammer, at our first campground with a swimming pool that is both free and open: 50 meters long, 8 lanes wide, alongside several smaller kiddie pools, all available to the public, but free to campers. We finally got our swim suits wet.

August 8

One of the first things we do in a new city is get acquainted with its layout and public transportation. This is particularly important if we have firm deadlines to meet for something, as we did in Helsinki, take-off point for our trip to St Petersburg, Russia.

And Helsinki presented some challenges. For one thing, it has more than one harbor, so we needed to determine at which one our ferry to St Petersburg was docked. (It was the west harbor, the same departure point for the day trip we hoped to take later to Tallinn, Estonia.) Also, we learned that the only bus route going from the central station to the harbor ran only about every 15-20 minutes, so timing became even more important. Still, after we’d learned all that, we could relax and explore the town for a couple of days before boarding the ferry: churches, museums, markets, shops and lots of walking, admiring architecture and people-watching (they’re not all blonde in Finland, but almost; and not all tattooed, but nearly so).

We found it really easy to get around Helsinki. The subway was about a two-minute walk from our very nice campground on the outskirts of town, and a 20-minute ride brought us right to the train station in the center of the city, where there were connections to all the trams and buses.

Helsinki Central Station, designed by Eliel Saarinen, 1919.

Once again we bought day passes so we could hop on and off public transportation as we wanted. They cost about $10 each, less than the cost of three rides.

Helsinki is the World Design Capital for 2012, and while it is heavily advertised here, we didn’t see that the title made much difference to us tourists. True, we visited a design museum and a showroom of that wonderful simple Scandinavian design, and in the markets there were lots of knitted items, real fur and Baltic amber jewelry . . . but somehow we expected more. Finally, on our last day in the city, we stumbled across an old porcelain factory/design showroom that had shops full of such innovative kitchen ware that we want to throw out everything we own and start over.

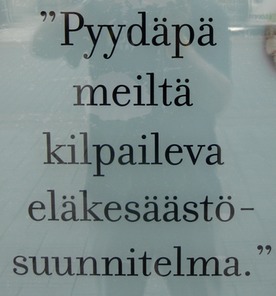

One of Helsinki’s major challenges is the language: Finnish is impossible for us. For one thing, it tends to add words together. During her stay in the hospital, for instance, Susan learned that Finnish makes “Turkuuniversityhospitalcafeteria” a single word. We can read it if we recognize the four words involved, but put that into Finnish with its K’s and V’s and umlauted vowels and doubled letters of all kinds and it becomes unintelligible. (A few examples:

Because Sweden once controlled Finland, Swedish remains one of the country’s two official languages, so many signs are in both:

Once in a while, they also use English: it’s the default language for the Dutch, Germans, Italians, Asians, and French (who just hate it, you can tell) . . . which is really nice for us.

After we’d returned from St Petersburg, we decided to tempt the Seasick Gods once again and took a day trip to Tallinn, Estonia, to visit the old medieval walled city. It was a rough and windy two-hour crossing both ways. As the passengers got off the boat at either end, it was clear that many people take these trips just to stock up on liquor at the duty-free store on the ferry: they come with folding rolling carts and leave with them loaded with cases of vodka, whiskey and wines.

We walked the cobbled streets of this city’s charming old town district, snapped lots of photos we won’t inflict on you (well, OK, but just one):

and visited a few churches and shops. Every other building is a restaurant; those that aren’t are souvenir shops. It is a popular day-trip destination: close to Helsinki, the old town small enough to see in a day, and, because Estonia is an EU nation, no passport control to slow anybody down (and of course there’s also the duty-free liquor).

We close with a “small world” story: in St Petersburg, our little canal boat tour group (seven) had included a young couple. Two days later, the male half of the pair was right behind us in line to board the ferry to Helsinki. Then, the day after that, as we left Tallinn, we saw him again, leaning against a doorway, as we made our way through the city wall to the boat. He was as astonished as we were to meet a third time. Apparently it was easier for him--but surely more expensive--to travel to Helsinki and do the “three-days-without-visa” trip to St Petersburg to visit his girlfriend than it would have been to go directly from Tallinn to St Petersburg.

August 6

This post has virtually nothing to do with camping in Europe. It is, rather, a brief description of our brief trip to St Petersburg, Russia.

Leaving Rover and the computer behind in the campground in Helsinki, we took an overnight ferry to St Petersburg. Before leaving the U.S., we had purchased a tour that allows entry into Russia without a visa for a 3-day stay with a firm exit date. It didn’t offer a way through customs, though, so after an interminable wait in that line, we were met by our young guide, Anna, and a driver and given a three-hour car tour of the city. It got us oriented, and we also received good advice about how to get around in the city. So after Anna dropped us off at the hotel in the early afternoon, we immediately headed for the ATM machine in the lobby, took out 1000 Russian rubles . . . and when we got to our room, we figured out we had just gotten the grand sum of $30. So on our way out, we got another 6000 rubles and left for the subway and the central city.

St. Petersburg is remarkably clean--even the heavily used subway, which had the longest escalators we have ever seen: fully a 2-½ minute trip from top to bottom. Many of the buildings are beautifully decorated, and the bright colors of their facades surprised us. But up close, most look to be in need of plaster repair and a fresh coat of paint. Every one has several large downspouts painted to match the building. Susan finally stopped and measured one: 8-½ inches diameter.

The main shopping street, Nevsky Prospect, is 8 lanes wide with few opportunities to cross, and is fronted by opulent buildings. Once we left Nevsky Prospect, though, we often could hardly tell whether we were passing by shops or not: there were few big display windows, lots of closed doors, and no markings to distinguish them from private entrances. Purely through stubbornness, we did find a theatre museum--it started on the third floor of the building--with four old ladies who made sure that we saw the whole thing . . . leading us from room to room, turning lights on and off as we entered and left, and seeing to it that we operated the wind and rain and thunder machines. The many scene design models ranged from antiquity to the high point of Russian theatre in the 1920s. But nothing was translated from Russian. In fact, outside of the hotel, we found very few clerks or wait staff who spoke any English.

We also visited three Orthodox churches: one where all the Tzars are buried, another with mosaics that rival Ravenna, Italy, a third filled with icons . . . and all of them over the top with gold leaf.

The Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood (!) marks the site of Tzar Alexander II's assassination.

To bring us back to earth, that evening we ate really bad fish and chips at the hotel and watched the Olympics.

The next morning Anna and a different driver took us on a tour of the Hermitage. What used to be an opulent winter palace for the Tzars is now a (still opulent) art museum.

Anna knew her way around, knew--and loved--Russian history, and knew what we wanted to see. Because we’d bought tickets ahead of time, we could avoid standing in line, and we skipped whole floors and wings of things we weren’t interested in (“Do you want to stay here after our time together is over?” she asked. “How much haven’t we seen?” we replied. “About 99%,” she said, smirking just a bit).

The Hermitage is an impressive place, but after four hours on our feet--accompanied by considerable Marxist aesthetics from Anna--we were ready for lunch. Anna recommended a restaurant we never would have discovered on our own: once again, there was nothing outside or on the door to indicate to an American that it was a restaurant, but it proved to be popular place with the locals: meat pies, fish pies, vegetable pies, and of course, dessert fruit pies. We had a delicious lunch for $17.75, including dessert and coffee.

And then we were on our own. Anna had assured us that the pickpocket and thug stories we’d read about were exaggerations, but we remained careful and alert anyway, and came away without incident. Later that afternoon, we took a boat tour in English that she had suggested. St. Petersburg is built on islands, in the midst of one major river and many small canals. The sky darkened as we waited for the boat, and within minutes of boarding a downpour drove us all inside. It rained off and on for the whole hour of the tour. Once again we had barely avoided getting soaked.

On Sunday morning we got out of the historical city center and went to a huge market in an older part of town. It went on for blocks and blocks: about a quarter of it in newer sheds, selling new goods, and the rest on tables and plastic sheets spread on the ground. Susan bought a child’s plastic sewing machine and considered it a find at $3.

We then walked and walked, unsuccessfully seeking two other museums/shops the Lonely Planet guide had mentioned, and finally returned to the hotel to get our luggage and be picked up by a third driver, who took us to the ferry.

Both overnight ferry crossings were smooth. It takes an hour just to get out of the huge harbor at St Petersburg and into open water. A large part of the ship is devoted to partying, with bars and casino and duty-free shopping staying open all night. We had dinner and fell exhausted into bed.

We arrived back in Helsinki at 8 a.m., and after another long wait through customs got back to Rover in the campground by 10. She was waiting just as we had left her: refrigerator running, and all the appropriate monitors glowing green. Best of all, Susan’s stomach has stopped complaining every times she feeds it. It feels good to be “home” again.

August 1

After four days in an isolation ward, Susan was finally released from the Turku University Hostpital with a functioning digestive system and a box full of antibiotics. (We are not any lighter in the wallet, though; they will send a bill to our home address in the US.) We immediately drove the 100 miles to Helsinki, got stopped in an hour-long traffic back up, and easily found the campground.

This is quite a nice place with large sites separated by flowering hedges. We immediately did two loads of laundry ($6 to wash, $6 to dry = $24). This was the first time we had been able to fully plug in the electricals since the power problem on the ferry, and we were relieved to find everything working properly.

In our limited touring of the city today, we had one really lovely moment. We had arrived at the Helsiniki (Lutheran) Cathedral just as a short English prayer service was ending. The fifty or so people there, some seated, others milling (quietly) about, still others standing still, received the blessing; and then the pastor invited us to sing together “Now Thank We All Our God.” We may have been the only ones who sang with her, and Susan was certainly the only one who knew all three verses (David almost did). That was the song we sang at our wedding some 45 years ago.

Tomorrow we leave for four nights on a side trip, by ferry, to St. Petersburg, Russia. Rover and the computer will not be accompanying us, so we want our fans--among whom you, dear reader, are chief--to be aware that we will not be posting for a few days.

July 27

We left really early for the ferry to Finland, once again crossing the bridge forbidden by our GPS, and driving less than two miles to the landing. They offered us use of electricity on board, which we gladly accepted: since we had to have the LP tank sealed in the “off” position, not having electricity would mean the refrigerator would be off or running on battery power for the twelve-hour trip. But when we returned to Rover at the end of the voyage, we found that something had tripped the main circuit breaker, and those few battery lights that remained were glowing red. (Surely there’s a moral to this story, but we don’t know enough about electricity to figure out what it is.)

Susan slept for ten hours of the twelve-hour trip and found a bit of time to look up her intestinal problem on the internet. It was just enough information to get her really worried. With a little help from the Viking Line information desk and a call to the US Embassy in Helsinki, we were instructed how to get to a hospital emergency room in Turku. So within 15 minutes of driving off the ferry, we were sitting in the waiting room, with Rover parked in a perfectly level and mostly free parking lot.

They did some blood tests, gave her some meds and told her to come back in the morning. So we stayed right in the parking lot overnight, running the engine for a while to bring the batteries back. In the morning they took x-rays and then transfered her by ambulance to a bigger hospital, where she had a CT scan and was admitted with a severe kidney infection. Rover is staying put right in the first hospital’s parking lot. Not at all what we had planned, but all part of the adventure.

July 25

We stopped on the outskirts of Stockholm for two nights in a crowded little campground (“crowded” means we tried to put down our awning to keep out the hot sun, but it hung over the narrow paved road by about 3 feet so we put it right back up again--no British “3 meters between caravans” in Sweden, thank you).

We picked this spot because we wanted to visit the Drottningholm palace and the Royal Theatre, which were within walking distance of the campground. It proved to be almost an hour’s walk, but a nice one through the forest and around a lake. The palace is the actual residence of the current king and queen, but much of it is open to the public just the same. Its vast grounds were inspired by Versailles, so it was quite spectacular.

But the real charm was the Royal Theatre. It is 250 years old and had been used regularly for about 100 years until the death of the king who had been its biggest patron. The theatre was then closed down, forgotten for years, and rediscovered only in 1920.

Nearly all of it is still in its original, unrestored condition, including painted scenery hundreds of years old. We were able to take a tour but were not allowed to take photographs. The most interesting fact is that scenery onstage can be completely shifted within seconds--and in full view of the audience--by a team of stagehands under the stage. (They accomplish this by turning a large wooden drum, around which ropes, connected to scenic trolleys, wrap and unwrap [got that? any questions? yes, this will be on the test.]) The whole thing was worth the walk . . . but we took the bus back to the campground anyway.

After Drottningholm, we went to our reserved camping place in the city of Stockholm. Getting to it meant going across a narrow concrete bridge with the GPS (in red) telling us we were a truck and what did we think we were doing, using this bridge? But we could see 60 motorhomes already on the other side, so we went anyway. This campground proved to be another gravel parking lot with motorhomes just lined up in rows. The facilities were OK, except that we had no WiFi for four days. But the bus and subway connections to get to the city center only two miles from us were only a short walk away (when it comes to campground facilities, convenience counts for a lot more than luxury with us).

According to a brochure we saw, Stockholm has 84 museums; it also has wonderful little--and big--shopping streets. It was a very busy place, and the good weather brought out people by the thousands. Once again we bought the Tourist Card for discounts and free admissions, and immediately set out to get our money’s worth. We visited three or four museums every day, took a boat tour and had guided tours of the National Theatre and the Opera House.

But the winner was the Vasa Museum. The Vasa was a huge warship built in 1628 and fitted out with 100 or so cannons. On the day it was launched, amid much celebration, with His Majesty the King looking on proudly, the wind filled its sails . . . it listed to one side . . . water poured into the open cannon port holes . . . and it sank to the bottom of the harbor: all this within about 20 minutes.

It stayed on the bottom for 333 years, until 1961, when it was found by divers and the project to raise it began. This work took two years, but now it is preserved and in a museum, along with all the artifacts that were brought up with it (including several skeletons). Everything but the food, fabrics and some of the wood had survived: tools, household goods, weapons, even some leather shoes. The museum’s low lighting made for poor photographs, but it was an amazing sight.

Susan has developed some stomach problems, but they haven’t really slowed us down much. Tomorrow the ferry to Finland will be a time to relax a little.

July 21

Before Norway slips out of our memory bank entirely--don’t laugh, it’s getting easier and easier for that sort of thing to happen--here’s a tutorial of miscellaneous notations for Americans driving around parts of Europe.

Followed, with your indulgence, by a rant.

1. The first bit of notation is specific to Norway and Sweden (and maybe Finland and Denmark, too, but we haven’t been there yet):

Numbers like these appear on parking signs and shop fronts; occasionally they’re even painted on buildings. They refer to things like a store’s opening hours or, as here, the times of day when you need to feed the parking meter. The first set of numbers refers to Monday through Friday hours; the second, in parentheses, is for Saturday; occasionally you’ll also see a second set of parentheticals for Sunday. (You won’t often see that second set in Norway because just about everything in the country is closed on Sunday.)

2. If you do find a grocery open on Sunday in Norway and make your way to the beer cooler, you may see this:

If the store is not in a high-density-tourist area, the helpful explanatory sign will be missing, leaving only the piece of canvas covering the beer cooler, as if to avoid taunting you with the sight of what you’re not allowed to buy on Sunday.

3. These next two are important, and they can be found all over Europe. They can cause more trouble than you might think, especially for American drivers, who aren’t used to them.

You’ll usually see the first sign (top left) along major highways. It means you are on a “priority” road, i.e., you don’t have to yield to traffic that is intersecting your road; instead, if the intersection is not controlled by a traffic light or a sign of some sort, you can drive through the intersection as if the other vehicles did have a stop sign.

And, after you’ve been driving in Europe and seen lots of black diagonal slashes on signs, you know that the sign on the bottom right one means you are on a “non-priority” road. Usually, you’ll see it on a highway that formerly had had priority status but has had that status suspended in a built-up area.

So what’s the big deal about non-priority roads? It’s this: when you’re on a non-priority road you are required to yield the right-of-way to any traffic entering your road from your righthand side.

The point of this practice, I’m told, is to reduce the speed of all traffic in a built-up area by making all drivers, regardless of the nature of the road they’re on, come to a stop when a vehicle approaches from their right (again, intersections controlled by traffic lights or some other signage are an exception).

One problem with this practice is that the poor driver--usually American--busily trying to cope with city traffic, pedestrians at crosswalks, signage in a foreign language, traffic signals in unfamiliar locations at intersections, etc., now has yet another thing to notice and keep track of: “Now I’m non-priority . . . OK, now I’m priority again . . . [crash] . . . oops, I guess I missed that last non-priority notice. . . .”

Another problem is that the whole system depends on every driver at an intersection knowing the “priority” status of every other driver’s roadway. If I’m on a non-priority road when I approach an intersection, my success at avoiding a collision may depend on whether I know the “priority” status of the guy approaching the intersection from my left: if (I know) the other road has priority, I yield; if (I know) it does not, I don’t; but (here’s the kicker) if I think I know but I’m wrong, there’s a 50-50 chance I’ll be pulling into the intersection in front of a driver who wasn’t planning to stop.

Happy motoring.

4. The Rant

Norway is justifiably proud of Henrik Ibsen. After all, the history books call him “The Father of Modern Theatre” (that should be “European” or “Western” Modern Theatre, but who’s counting).

And so:

--while he was living abroad for decades, building his international reputation by churning out masterpieces that trashed his native land for its philistinism and provincialism (and weather), his fellow countrymen bore it in silence;

--when toward the end of his life he deigned to return to Norway to live, they showered him with honors;

--when every noon he entered the Grand Cafe in Oslo for his customary midday meal, they rose from their tables and remained standing until he was seated (or so the waiter there assured us when we asked which was his table);

--at his death, they established three museums to him in places he’d lived around the country. (And, maybe most remarkably, they saw to it that the commentaries on his life and works in these museums were exceptionally insightful and the tour guides staffing them extraordinarily knowledgeable about his life and personality.)

--And, of course, they also erected his statue in front of the National Theatre in Oslo

and bade the artists working there keep his plays alive so that (as they love to point out . . . but modestly, ever so diffidently) he will continue to be the second-most-performed playwright--trailing only Shakespeare. And that, unlike the “Father of Modern Theatre” business, is not only in Europe or the West but throughout the world.

So then: Truly, Ibsen was a remarkable talent, and Norwegians are rightfully proud of his legacy and should do what they can to keep it alive around the land. Most particularly, they should do so at the country’s flagship dramatic institution, the National Theatre in Oslo (where they erected his statue, remember).

Ahem.

About that National Theatre.

But first, about Oslo:

Oslo is, of couse, the capital city of Norway, and many roads lead to it.

And Norway is one of the many countries in Europe that (virtually) shuts down during the month of July and sends (nearly) everybody off on vacation.

And because Oslo is the capital city and many roads lead to it,

--and because Norwegians are a really patriotic people,

--and also because Oslo is pretty far south (pretty far for Norway, anyhow), so the weather there might be expected to be warmer than most other places in the country . . .

for all these reasons, lots and lots of Norwegians spend at least part of their vacation … in Oslo.

(And lots of other Europeans come there, too, as well as quite a few Americans, because it’s a really lovely city, and because maybe they can learn somthing--you think?--from the people of Norway about things like . . .

oh, I don’t know . .

things like how to keep their citizens alive longer at less cost

and how to give science a leading role in establishing policies about their environment

and how to discourage drunk driving by taking away their licenses at the slightest whiff of alcohol instead of this “.06,” “ .08” crap,

and how to encourage healthy family life with maternity and paternity leaves at full pay and subsidized early childhood education and don’t get me started. . . .

(But I digress.

Where was I?

Oh, yes.)

So the point is--the points are--

(a) Ibsen continues to be really important to Norwegians and to the country’s cultural identity;

(b) there are hoardes of Norwegians in Oslo in July;

(c) Oslo is where the National Theatre, dedicated to the preservation of Ibsen’s works, is; and

(d) seeing a first-class production of one of a guy’s plays--instead of just reading it, say, or, God help us, being reduced to talking about it in a classroom--seeing a play is a really good way of coming to appreciate the work and how the guy’s mind works.

(Can you see where I’m going here?)

Conclusion: July would be an awfully good time for Norway’s National Theatre to be busy as hell, doing Ibsen plays as well as they can do them. . . .

But they don’t do it!

The National Theatre is closed.

And not just in July: it’s closed all summer!!

WHAT’S UP WITH THAT?